Chapter 1 Introduction to Python

Python is an extremely powerful open-source programming language. It is considered a “high-level”, “general purpose” language in that offers strong abstractions on computer instructions (and in fact often reads like badly-punctuated English), and can be used effectively for a wide variety of purposes. Python is one of the most popular programming languages in the world, and very approachable for beginners and experts alike. Python will be the primary programming language for this course.

1.1 Programming with Python

Python is a high-level, general-purpose programming language that can be used to declare complex instructions for computers (e.g., for working with information and data). It is an open-source programming language, which means that it is free and continually improved upon by the Python community.

- Fun Fact: Python is named after British comedy troupe “Monty Python”, because it seemed like a good idea at the time.

So far you’ve leveraged formal language to give instructions to your computers, such as by writing syntactically-precise instructions at the command line. Programming in Python will work in a similar manner: you will write instructions using Python’s special language and syntax, which the computer will interpret as instructions for how to work with data.

Indeed, Python is an interpreted language, in that the computer (specifically the Python Interpreter) translates the high-level language into machine language on the fly at the time you run it (“at runtime”). The interpreter will read and execute one line of code at a time, executing that line before it even begins to consider the next. This is in contrast with compiled languages (like C or Java) that has the computer do the translation in one pass, and then only execute the program after the whole thing is converted to machine language.

- This means that Python is technically a little slower to execute commands than C or Java because it needs to both translate and execute at once, but not enough that we’ll notice.

While it’s possible to execute Python instructions one at a time, it’s much more common to write down all of the instruction in a single script so that the computer can execute them all at once. Python scripts are saved as files with the .py extension, You can author Python scripts in any text editor (such as VS Code), but we’ll also write and run Python code in an interactive web application called Jupyter.

1.1.1 Versions

Python was first published by Dutch programmer Guido Van Rossum in 1991. Although the language is open-source (and so can be contributed to by anyone), Van Rossum still retains a lot of influence over where the language goes, and is known as Python’s “Benevolent Dictator for Life”.

Version 2.0 of Python was released in 2000, and version 3.0 was released in 2008. However, unlike with many other programming languages that release new versions, Python 2 and Python 3 are not compatible with one another: Python 2 code usually won’t execute with Python 3 interpreter, and Python 3 code usually won’t execute with a Python 2 interpreter.

Python 3 involved a major restructuring which included a number of “breaking” changes to core parts of the language. The most noticeable of these are that all text strings support Unicode (non-English characters), print is a function not a statement, and integers don’t use floor devision (these concepts are discussed in more detail below).

In short, Python 3 is considered the “current” version, and Python 2 is considered the “legacy” version (and is not longer supported). However some few external libraries that failed to update to Python 3. Thus in practice there are two incompatible versions of Python that are used in the world. See Python2orPython3 for more details.

- In this book, we will be using Python 3, particularly as it fixes some issues that often trip up beginners, is supported by all major libraries in a more effective way, and will still be supported in the near future!

1.2 Running Python Code

Python scripts (programs) are just a sequence of instructions, and there are a couple of different ways in which we can tell the computer to execute these instructions.

1.2.1 Jupyter Notebooks

One of the most popular and effective way of writing and running Python code is to utilize a Jupyter Notebook. A Jupyter Notebook is a web appplications (that runs in your web browser) and provides an interactive platform for running Python code: you are able to write and execute Python code write in the browser.

- Jupter is a portmanteau of “Julia”, “Python” and “R”, which are the programming languages the application was designed to support. Each notebook runs on an individual kernel or language interpreter; you’ll want to be sure you’re running a Python 3 kernel for this course.

Code is authored in individual “notebooks”, which are collections of cells (blocks of code or text). Cells can also include Markdown (text) content, allowing notebooks to act as interactive documents with embedded, runnable code.

The Jupyter program is part of the Anaconda package, and so should be installed along with Python. You can launch it from the Anaconda Navigator by selecting it from the menu and clicking the “Launch” button (it will then open up a command shell prompt and start it from ther).

This will open up your web browser with an interface to create or open a notebook relative to the folder you started Jupyter from:

Opening notebook animation, from the official documentation

Note that you can also start Jupyter directly from the command line with:

jupyter notebookYou can open a particular notebook (which are saved as files with the .ipynb extension) by passing the notebook name as an argument:

jupyter notebook my-notebook.ipynb- To stop running the Jupyter notebook server, hit

ctrl-cin the terminal and follow the prompts.

Jupyter notebooks are made up of a series of cells, each representing a set of code or text. Cells by default are used for Python code, but can also be set to use Markdown by selecting from the dropdown menu.

You can type code directly into the cells, just as if you were typing into a text editor. In order to execute the code in a cell, press shift-enter or select Cell > Run Cell from the menu. Any output from the cell will appear immediately below it. You can add new cells by hitting the “plus” button on the toolbar.

- Pro-tip: There are lots of keyboard shortcuts available for working with cells. Click the keyboard icon on the toolbar to see a list of shortcuts.

1.2.2 On the Command Line

It is also possible to issue Python instructions (run lines of code; called statements) one-by-one at the command line by starting an interactive Python session within your terminal. This will allow you to type Python code directly into the terminal, and your computer will interpret and execute each line of code (if you just typed Python syntax directly into the terminal, your computer wouldn’t understand it).

With Python installed, you can start an interactive Python session on a by running the python program (simply type the python command if you’ve installed it on the PATH via Anaconda).

- On Windows using the Git Bash shell, you may need to utilize winpty to connect the Bash shell to the Python output: see here for an example). On my machine, using

winpty pythonworks well.

Note that if you haven’t installed Python via Anaconda, or have multiple versions installed, you may need to use the python3 command to run a Python 3 session.

On the iSchool lab machines, you can switch from Python 2 to Python 3 using the command:

source activate python3The python command will start the interactive session, providing some information about the version of Python being run:

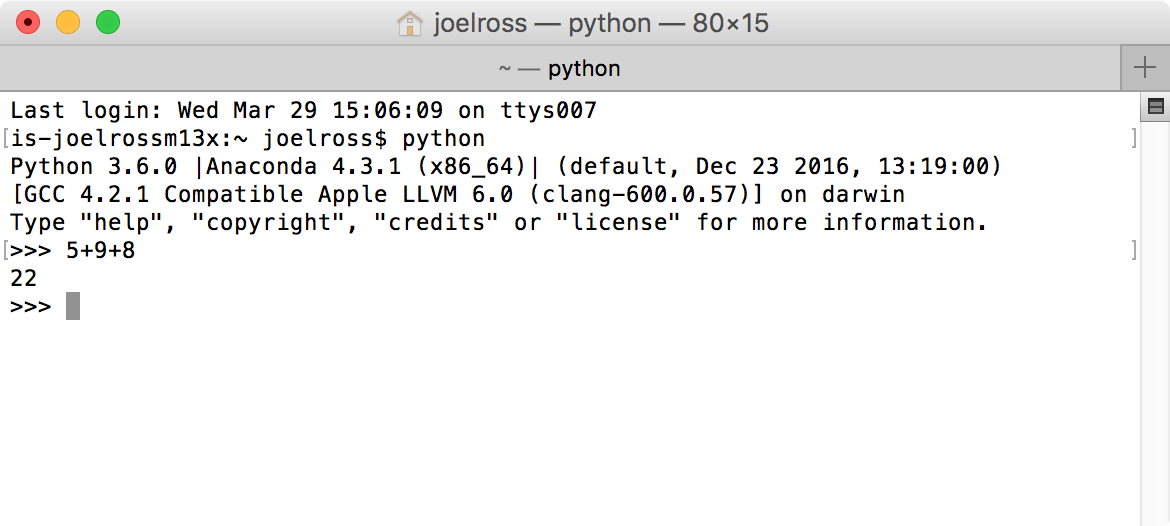

Interactive Python session

Once you’ve started running an interactive Python session, you can begin entering one line of code at a time at the prompt (>>>). This is a nice way to experiment with the Python language or to quickly run and test some code.

- You can exit this session by typing the

quit()command, or hittingctrl-z(followed by Enter on Windows).

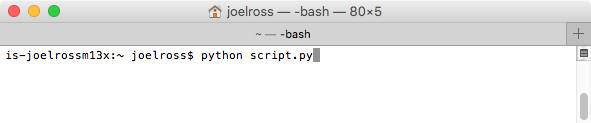

It is more common though to run entire scripts (.py files) from the command line by using the python command and specifying the script file you wish to execute:

Run Python script from the command line

This will cause each line in the script to be run one at a time. This is the “normal” way of running Python programs: you write Python scripts using an editor such as VS Code, and then execute those scripts on the command line to see them in action.

1.4 Variables

Since computer programs involve working with lots of information, we need a way to store and refer to this information. We do this with variables. Variables are labels for information; in Python, you can think of them as “nametags” for data. After giving data a variable nametag, you can then refer to that data by its name.

Variable names can contain any combination of letters, numbers, or underscores (_). Variables names must begin with a letter. Note that like everything in programming, variable names are case sensitive. It is best practice to make variable names descriptive and informative about what data they contain. a is not a good variable name. num_cups_of_coffee is a good variable name. To comply with Google’s Style Guidelines variables should be in “snake_case”: all lower-case letters, separated by underscores (_).

We call putting information in a variable assigning that value to the variable. We do this using the assignment operator =. For example:

# Stores the number 7 into a variable called shoe_size

shoe_size = 7- Notice: the variable name goes on the left, the value goes on the right!

- It is good style to put white spaces around the

=operator to keep it easy to read.

You can see what value (data) is inside a variable by either typing that variable name as a line of code, or by using Python’s built-in print() function (more on functions later):

print(shoe_size)

## 7You can also use mathematical operators (e.g., +, -, /, *) when assigning values to variables. For example, you could create a variable that is the sum of two numbers as follows:

x = 3 + 4- A combination of variables, values, operators, or functions that the interpreter needs to evaluate is called an expression.

Once a value (like a number) is assigned a variable—it is in a variable—you can use that variable in place of any other value. So all of the following are valid:

x = 2 # store 2 in x

y = 9 # store 9 in y

z = x + y # store sum of x and y in z

print(z) # 11

z = z + 1 # take z, add 1, and store result back in z

print(z) # 12Important despite using an equal sign (=), variable assignments do not specify equalities! Assigning one variable to another does not cause them to be “linked”; changing one variable will leave the other unchanged:

x = 3

y = 4

x = y # assign the value of y (4) to x

print(x) # 4

y = 5

print(x) # 4;Changing the value named y does not change the value named y, even if the value from y was put into the x variable at some point.

- Tip: when reading or writing code, try to think “x is assigned 3” or “x gets the value 3”, rather than “x equals 3”.

1.4.1 Data Types

In the examples above, we stored numeric values in variables. Python is a dynamically typed language, which means that we do not need to explicitly state what type of information will be stored in each variable we create. The Python interpreter is intelligent enough to understand that if we have code x = 7, then x will contain a numeric value (and so we can do math upon it!)

You can “look up” the type of a particular value by using the type() function:

type(7) # integer

## <class 'int'>

type("Hello") # string

## <class 'str'>- Type is also referred to as

class(i.e., “classification”). Classes are ways of structuring information and behavior in computer programs. Classes are discussed in more detail later.

There are a number of “basic types” for data in Python. The two most common are:

Numeric Types: Python has two data types used to represent numbers:

int(integer) for whole numbers like7andfloatfor decimals like3.14(because the decimal point is “floating” in the middle).We can use mathematical operators on numeric data (such as

+,-,*,/, etc.). There are also numerous functions that work on numeric data (such as for calculating sums or averages). You can mix and match ints and floats in mathematical expressions; the result will be a float if either of the operands are floats. Division (/) always produces a float; use the “integer division operator”//to force the result to be a whole number (rounded down).Strings: Python uses the

str(string) type to store textual data.strvalues contain strings of characters, which are the things you type with a keyboard (including digits, spaces, punctuation, and even line breaks). You specify that some characters are a string by surrounding them in either single quotes (') or double quotes (").# Create a string variable `famous_poet` with the value "Bill Shakespeare" famous_poet = "Bill Shakespeare"Note that string literals (the text in quotes) are values just like numeric literals (numbers), so can be assigned to variables!

Using “triple-quotes” will allow you to specify a multi-line string:

message = """Dear Professor, My dog ate my homework. Thank you, A. Student """

Strings support the

+operator, which performs concatenation (combining two strings together). For example:# concatenate 3 strings. The middle string is a space character full_name = "Bill" + " " + "Shakespeare"The operands must both be strings. Also notice that concatenating strings doesn’t add any additional characters such as spaces between words; you need to handle such punctuation yourself!

There are many built-in functions for working with strings, and in fact strings support a variety of functions you can call on them. See Functions for details.

There are many other data types as well; more will be introduced throughout the remaining modules.

Helpful tip: because variables can any type of data, it is often useful to name variables based on their data type. This helps keep the purpose of code clear in your mind, and makes it easier to read and understand what is happening:

password_num = 12345 # variable name indicates a number, so can do math on it

password_str = "12345" # variable name indicates a string, so can print itIt is possible to convert from one type to another by using a type converter function, which is usually named after the type you wish to convert to:

int(3.14) # 3 (converted from a float to an int)

int(5.98) # 5 (takes the floor value instead of rounding)

float(6) # 6.0 (converted from an int to a float)

str(2) # "2" (converted from an int to a str)

int("2") # 2 (converted from a str to an int)

int("two") # ValueError! (cannot convert)This is particularly useful when you wish to include a number in a string:

favorite_number = 12

message = "My favorite number is "+str(favorite_number)

print(message) # My favorite number is 121.5 Getting Help

As with any programming language, when working in Python you will inevitably run into problems, confusing situations, or just general questions. Here are a few ways to start getting help.

Read the error messages: If there is an issue with the way you have written or executed your code, Python will often print out an error message. Do you best to decipher the message (read it carefully, and think about what is meant by each word in the message), or you can put it directly into Google to get more information. You’ll soon get the hang of interpreting these messages (and how to resolve common ones) if you don’t panic when one appears. Remember: making mistakes is normal!

Documentation: Python’s documentation is pretty good: very thorough and usually contains helpful examples. The only problem is that it can occasionally be too detailed for beginners, and can sometimes be hard to navigate (where to find information is not immediately obvious in some situations). Searching the documentation (potentially through Google) is a good way to narrow down what you’re looking for.

Searching the Internet: When you’re trying to figure out how to do something, it should be no surprise that Google is often the best resource. Try searching for queries like

"how to <DO THING> in Python". More frequently than not, your question will lead you to a Q/A forum called StackOverflow, which is a place to find potential answers.While sites such as StackOverflow is a great place to find answers, those answers often assume a prior understanding of programming, or make use of advanced/trickier syntax and methods because it’s “cooler”. In general, I discourage beginning students from looking at StackOverflow. The answers you find will often confuse you more; and while sample code may “work”, it may not do it in a way that you understand (or in a way that’s appropriate for the class). StackOverflow is good for finding answers, but it’s not good for learning. Checking in with your instructor is better for that!

Many basic questions have already been asked/answered on Q&A sites like StackOverflow. However, don’t hesitate to post your own questions to StackOverflow. Be sure to hone in on the specific question you’re trying to answer, and provide error messages and sample code as appropriate. I often find that, by the time I can articulate the question enough to post it, I’ve figured out my problem anyway.

- There is a classical method of debugging called rubber duck debugging, which involves simply trying to explain your code/problem to an inanimate object (talking to pets works too). You’ll usually be able to fix the problem if you just step back and think about how you would explain it to someone else!

Resources

Python is an incredibly popular programming language and is especially accessible to new programmers. As such, there are a lot of resources available for learning how to program in Python. While this book will cover most of the details you need, below are a number of other effective resources below in case you need further help. Note that you’ll need to reference Python 3 materials.

- Think Python (Downey): a free, friendly introductory textbook for learning Python. You should definitely read Chapter 1, which is a great overview of programming in general.

- Python for Everybody (Severance): a remixed version of the above book, with a focus on Information Sciences. See in particular the interactive version. Chapter 1 of this book is also a very good read.

- Automate the Boring Stuff with Python (Sweigart): another good free textbook

- Python for Non-Programmers Index: an extensive list of resources and materials for learning to program with Python. The textbooks and interactive courses are all good options.

- Official Python Documentation

- Google’s Python Style Guide

Specific resources for the material in this module:

1.3 Comments

Before discussing how to program with Python, we need to talk about a piece of syntax that lets you comment your code. In programming, comments are bits of text that are not interpreted as computer instructions—they aren’t code, they’re just notes about the code! Since computer code can be opaque and difficult to understand, we use comments to help write down the meaning and purpose of our code. While a computer is able to understand the code, comments are there to help people understand. This is particularly imporant when someone else will be looking at your work—whether that person is a collaborator, or is simply a future version of you (e.g., when you need to come back and fix something and so need to remember what you were even thinking). Comments should be clear, concise, and helpful—they should provide information that is not “obvious” from the code itself.

In Python, we mark text as a comment by putting it after the pound/hashtag symbol (

#). Everything from the#until the end of the line is a comment. We put descriptive comments immediately above the code it describes, but you can also put very short notes at the end of the line of code (preferably following two spaces):